Dad would be 98-years old today. He died in 1994, however. The heart attack got him just two-months after mom went. How I loved them. For dad, these are a few random memories—out of a million more. For laughs, lessons and so much more—these are thanks that I owe my dad.

It was a happy novelty to find dad in bed on weekends after the war. He was the kind of guy who never had a hair out of place on work days. We could give his hair a tousle when we caught him in bed and tell him he looked funny. “I’m just an old poo-doo man,” he told us, shaking his head with slack cheeks. I rubbed my face against his whiskers, and said “You’re a poo-doo man, dad.”

He was up early during the week and off to catch the bus. Once I caught him brushing his teeth before breakfast and I told him he should brush after eating. He smiled at me and tousled my crewcut. “You are right, Timmy Boy. There is a better way. But the main thing is that they get brushed,” he said.

When he read stories to us, he often read the words backwards. When we corrected him, he exclaimed, “Pah!” And he read properly for a bit until another “Pah” kept us laughing.

Noises were laugh generators, and dad’s “tok” was the most famous. Dad could crack his tongue off the roof of his mouth in a thunderous snap. We all mastered it. So our house was often filled with loud pops—none louder that dad’s. He deafened us.

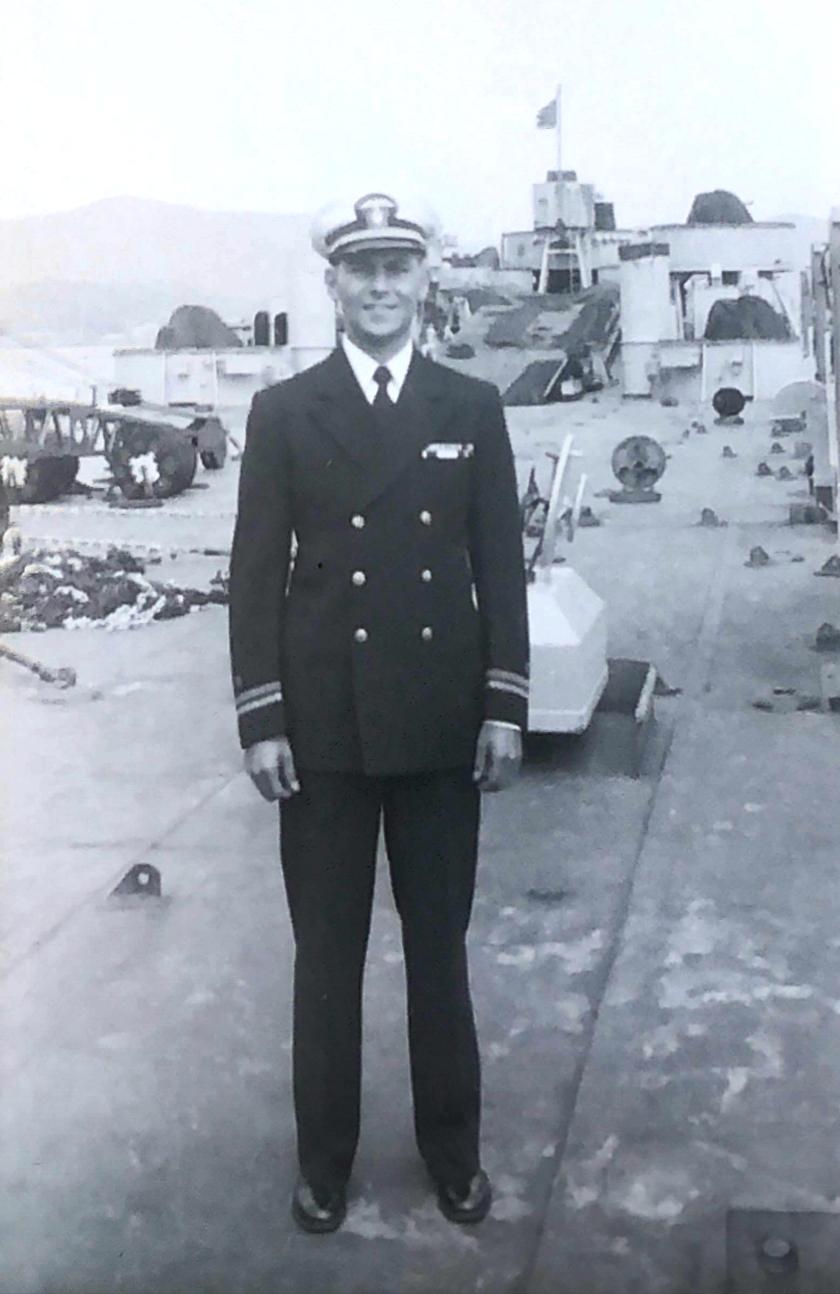

Dad took us with him on Saturdays to give mom a break. We tagged along planting roses on the Lewis and Clark campus. Or shadowed him to Swan Island where he typed reports at the Naval Reserve Training Center. We ran the halls while he typed. The building was round, reminiscent of a miniature Pentagon. Most commonly, we tagged along to the Phone Company, dad’s real work—on SW 4th and Oak. We loved riding the elevators and spying on the ant-people scurrying along the streets below.

One ride down Belmont, I got under his skin. I had mastered the arm fart and tooted one fart sound after another from the backseat in the ’52 Plymouth. Dad was good at jokes and funny noises, so I was a little surprised when he objected to my fake farts. But dad could put his foot down in just the right way. “Now cut that out,” he bellowed in mock anger, sounding like Phil Silver’s TV character Sargent Bilko. I knew when enough was enough, so I rode across the Morrison Bridge in silence. Dad parked on the east side of Front Ave. (now Naito Parkway) so we had to take the pedestrian tunnel. It crossed under Front Ave. at Morrison. The tiled walls made quite an echo chamber, and dad encouraged me, saying, “This would be a good place for you to make your noise, Timmy Boy.” I was confused, having just been chastised on the drive down. But I wasn’t going to let the green light go to waste. So I reached under my shirt and lost no time to start pumping out armpit farts. “Not that noise!” Dad pointed out the obvious. Suddenly, two-plus-two became four, and I immediately began “tok-king” my way under Front, and dad even let loose a Howitzer “tok” or two of his own.

Remembering dad can’t go far without recalling when he saved my life! It happened on the day of dad’s Phone Company picnic. I was a five-year-old. It was mid-summer and I had a noisemaker in hand, the kind that buzzed out a rasping honking noise when you blew into it. Well, I doubled its efficiency by inhaling through the mouthpiece as well as blowing through it. My pride in creating endless noise with both cycles of my breath came to a startling halt. One deep inhale sucked the metal vibrator right out of the toy and down my throat, where it lodged painfully in my throat’s soft windpipe. Breathing ceased. Panic owned me.

The next thing I knew, dad was there. I have no idea how he appeared so fast. His face was right in front of me. His furrowed brow so deeply engaged. My panic gone. Just that fast, his fingers reached down my gullet, found the disc and tore it free. It hurt to breathe. Such a welcome sore throat. And dad’s face, a picture of relief.

At the picnic, I was certain dad would win the men’s footrace. He was fast. I watched him workout at the Grant High track. But that day at Dodge Park, he got boxed in and finished in the pack. I told him how much I wanted him to win the race. My dad told me, “Don’t worry, Timmy Boy. It’s okay. Under the circumstances I did the best I could.”

That he did.

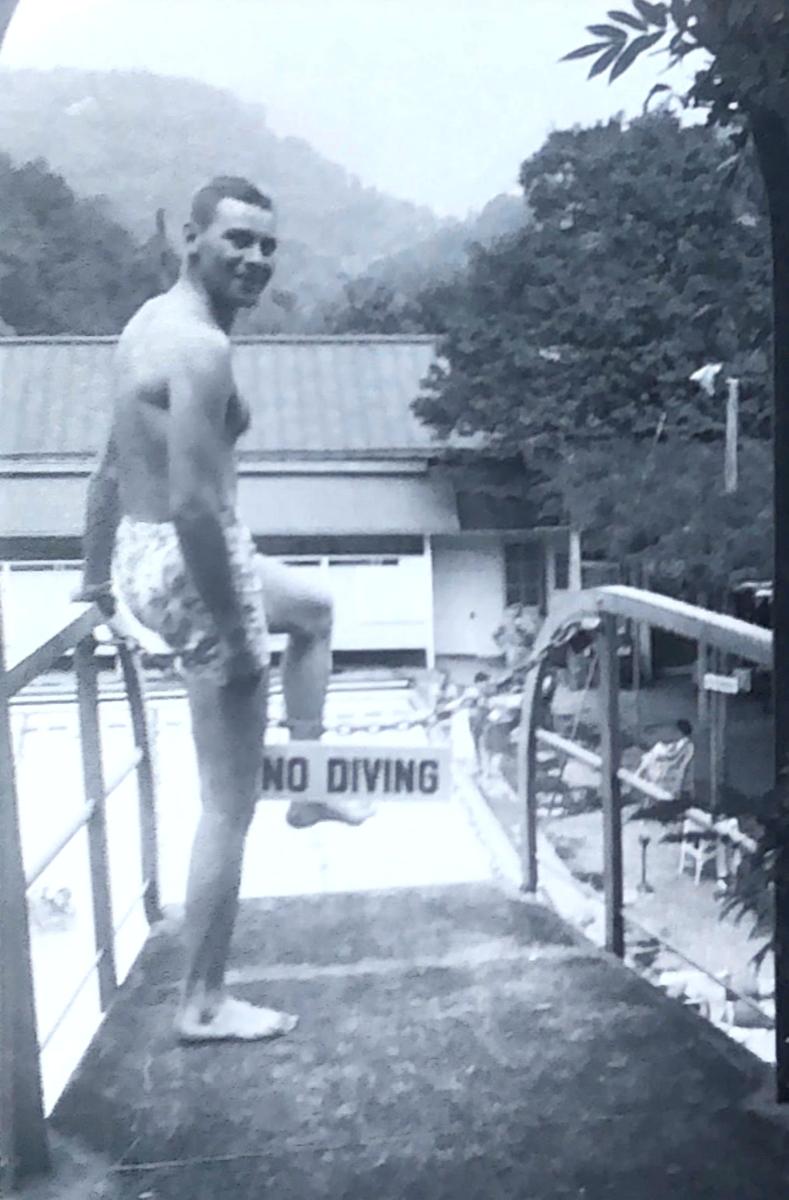

Photos: Brown family album